4 ways to describe turnover, and how it helps our lakes

What causes lake turnover?

Turnover is like a dog learning to roll over.

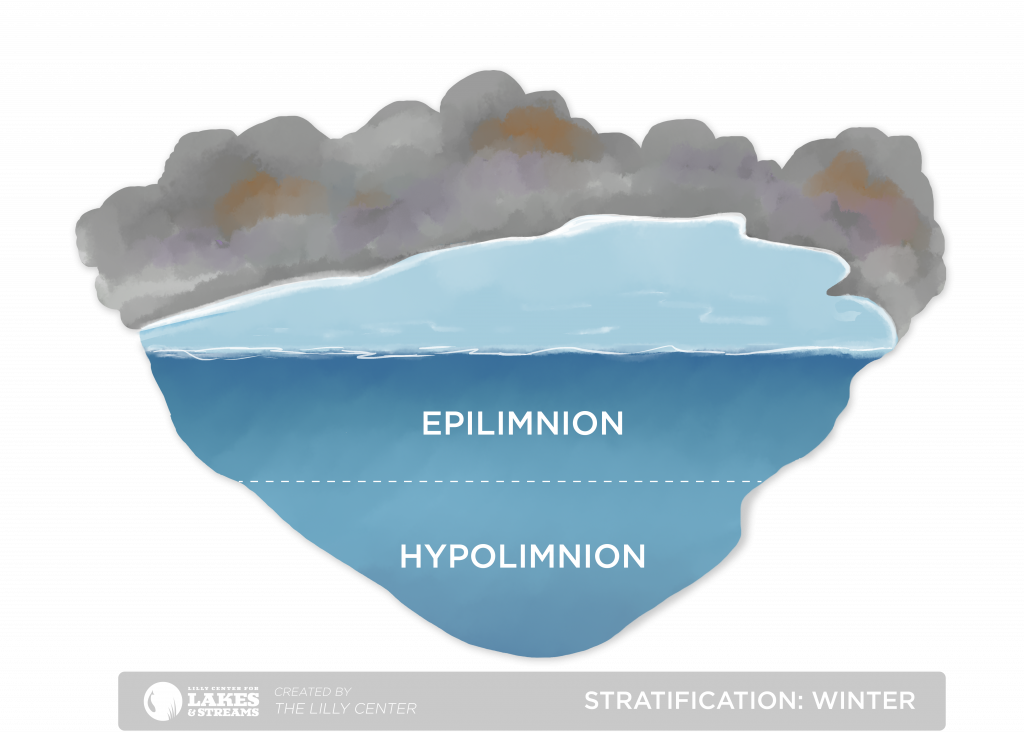

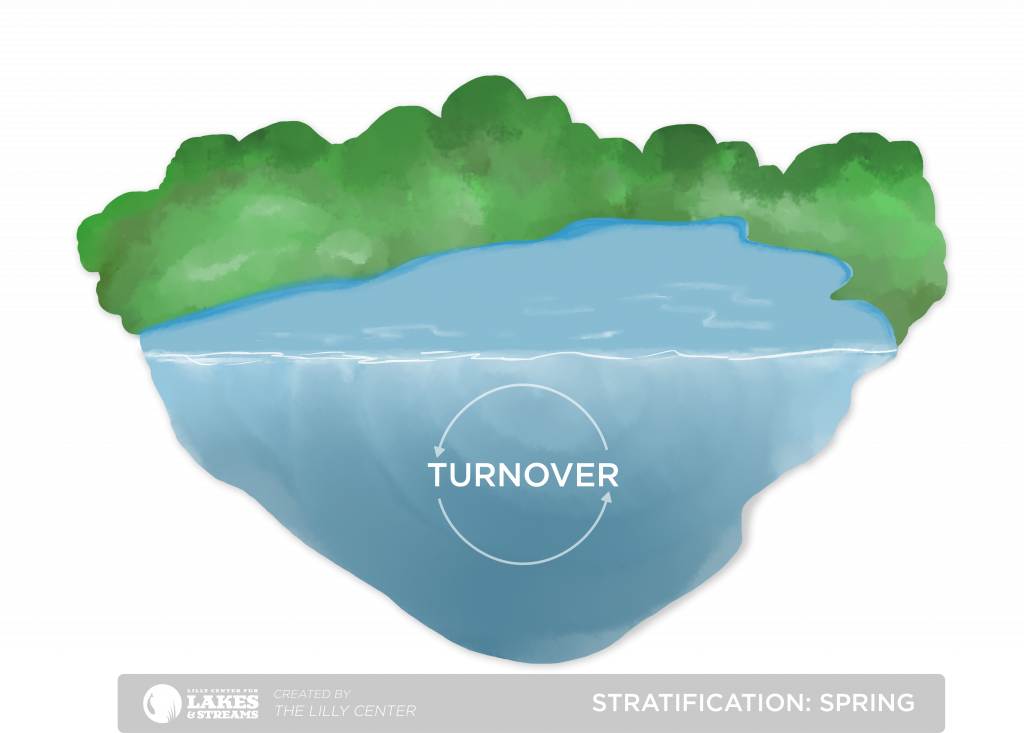

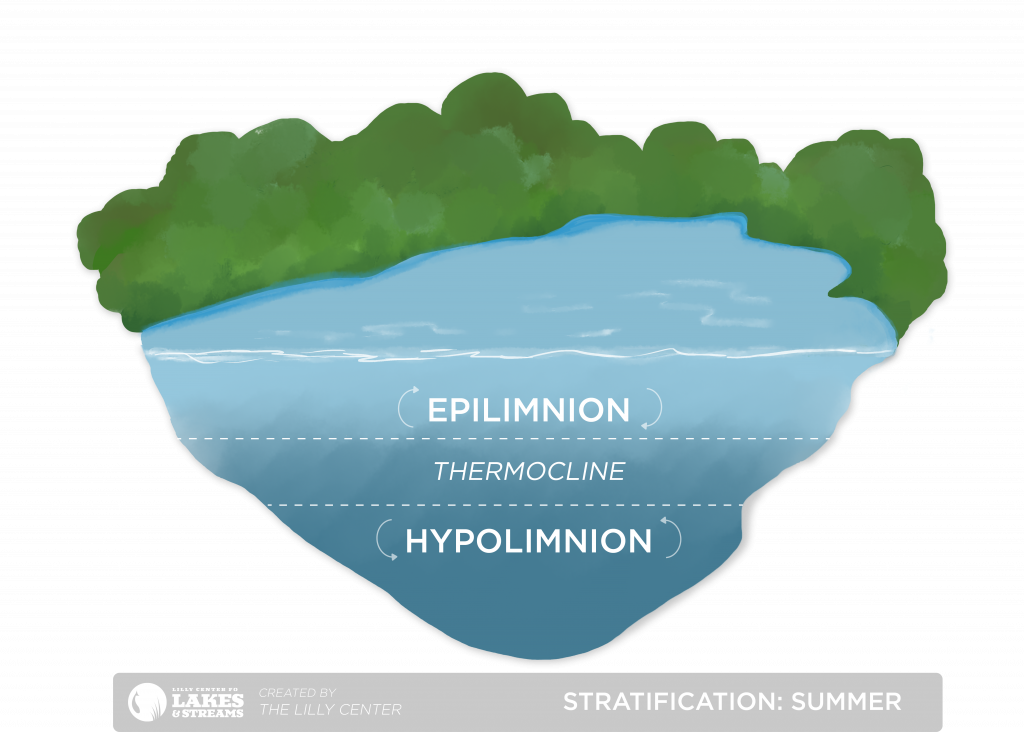

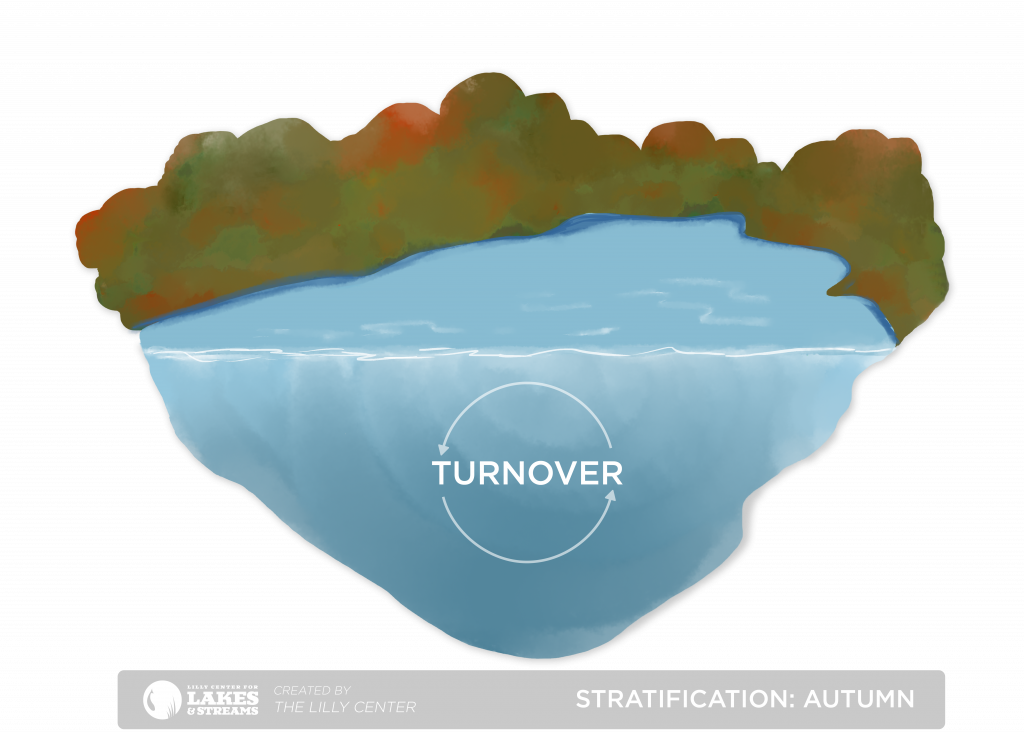

Fall and spring turnover are natural phenomenon that cause the top layer of the lake (the epilimnion) and the bottom layer of the lake (the hypolimnion) to trade places. In the fall, this phenomenon happens when the temperature in the air drops. The epilimnion then cools to a temperature that balances with the density of the hypolimnion, allowing them to “intermingle.” The opposite occurs in the spring: the air temperature rises, warming the surface water while the bottom grows cooler.

The two layers could not intermingle without the wind!

Turnover is much like a dog learning to roll over: As he pushes himself to one side, his underbelly begins to show.

This process is most noticeable in the fall. As winter approaches, a constant breeze begins to move over the surface of the lake. The wind pushes the surface water from one shore to the other, and as this happens, the hypolimnion moves upward to replace the water that is moving across to the other shore. Once it reaches the other shore it gets pushed downward to replace the hypolimnion that moved up to the other side of the lake. The lake “rolls over” in this way in an ongoing cycle until it freezes over.

In both the fall and the spring, turnover affects three major aspects of the lake environment: oxygen, algae, and phosphorus.

How does dissolved oxygen get into water?

Turnover is like folding chocolate chips into cookie dough.

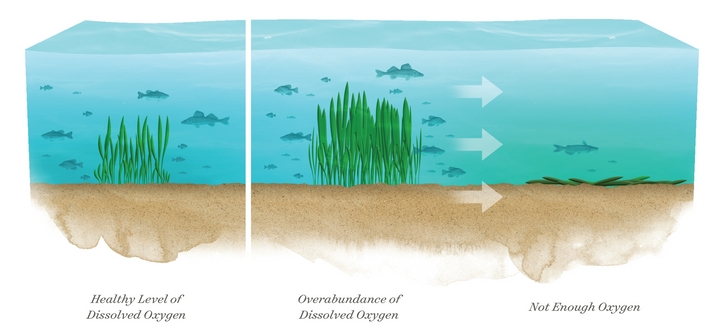

The hypolimnion routinely runs low or out of dissolved oxygen. There are many explanations for this but one main reason is decomposition, such as bacteria breaking down organic matter.

Turnover causes oxygen to mix into the lake, much like when you stir or fold chocolate chips into cookie dough batter. Turnover breaks down the temperature boundary and moves oxygen-rich surface water to the bottom and oxygen-starved bottom water to the top. Once in the water, it becomes dissolved oxygen.

Moving dissolved oxygen to the hypolimnion is not only crucial to the lake, but also to the fish who live there.

Fish and most other aquatic critters rely on dissolved oxygen to survive. If too much muck builds up and dissolved oxygen is not replenished, fish will be forced to move toward the surface. For some cold-water fish species, like cisco, this is bad news!

How turnover impacts algae and phosphorus

Turnover is like being at the mall … or at a fair.

Turnover is a natural way the lake cleans up harmful bacteria and algae. It carries dead algae down into the depths of the lake where there is less sunlight, helping to prevent algae growth. You can think of it as an escalator, moving the algae cells from the top of the lake to the bottom. There, algae is eaten or decomposed.

Turnover also helps clean up excess phosphorus.

As turnover forces iron (which naturally exists in our lakes) toward the hypolimnion, the iron interacts with phosphorus. As it falls to the bottom, the compound is deteriorated by oxygen and anaerobic bacteria. This process is similar to a Ferris wheel. The phosphorus and iron “ride” to the epilimnion and back down to the hypolimnion. Algae blooms are fueled by phosphorus, so the mixing cycle can reduce the conditions for a bloom.

Turnover happens twice a year in our region.

And each time, the lake and its inhabitants breathe a watery sigh of relief as dissolved oxygen is replenished. Did you know that dissolved oxygen levels are one of the many parameters tracked by the Lilly Center research team? Discover the current state of local lakes today.