Everything you need to know about the Tippecanoe River

Did you know that “Tippecanoe” is derived from the Miami Indian word for “buffalo fish”? The species was abundant in the Tippecanoe River when it was named and can still be found today.

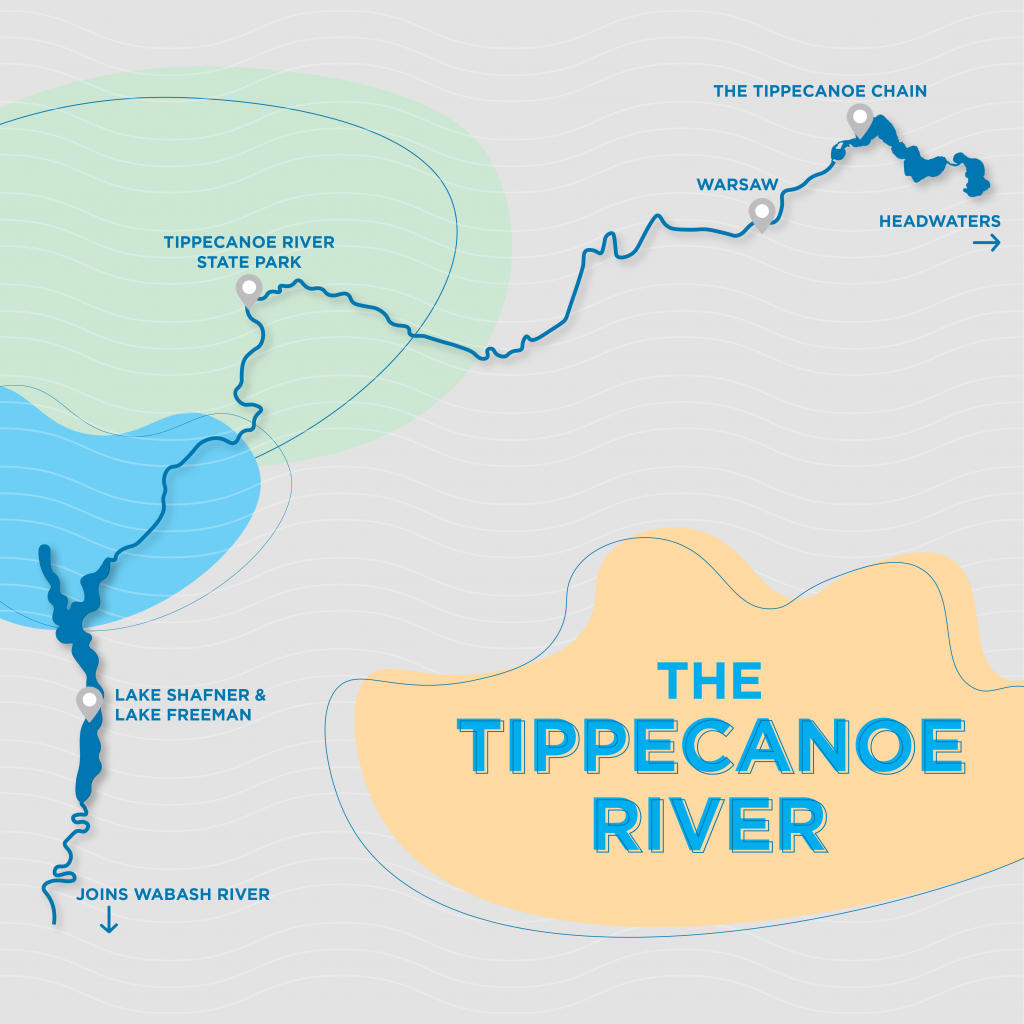

The Tippecanoe is a fixture in Kosciusko County. The river flows nearly 200 miles from its headwaters just east of Kosciusko County to northern Lafayette, where it joins the Wabash River. The Tippecanoe is gentle, curving, neither too deep nor too shallow. Its floodplains nourish both forests and flatlands. In its current, the river carries many endangered species.

Although the lesser-known of Indiana’s rivers, the Tippecanoe is irreplaceable. It is called the “river of lakes” due to the many bodies of water it flows through. Several of those are in Kosciusko County!

What does “headwaters” mean?

Headwaters refers to the furthest point where multiple smaller bodies of water (called tributaries) merge to form a single channel. A river is also fed by groundwater, precipitation and snowmelt. It all flows to a single drainage point – typically an ocean or sea. In the Tippecanoe’s case, it joins the Wabash before heading to the Gulf of Mexico.

Because rivers behave as systems, what happens upstream and in the surrounding watershed will impact downstream areas. A clear example of this is a post-storm logjam. Downed branches, uprooted trees and other debris create barriers. They prevent water from flowing normally, which can force the water to form a new path.

A river is less prone to rerouting than a stream. But it will adjust its course to find the most direct path through its basin!

Sometimes, a river that finds a more direct path will leave behind an oxbow lake. These waterbodies have a distinctive U-shape. It is generous the call them lakes, actually, as most oxbows have no natural inflowing or outflowing streams. They become wetlands, serving as rich wildlife habitats in the meantime.

If you would like to see a Tippecanoe River oxbow lake in person, visit Tippecanoe River State Park in Winamac, Ind.!

What makes a river different from a stream?

In general, a river is wider, deeper and more well-defined than a stream. A river often has a more permanent route, too. It carves a course based on the type of rock and soil it travels through, sometimes meandering, sometimes flowing in a straight line.

In our state, Miami soil comprises much of the northern-and-central regions. It is somewhat silty, somewhat loamy. Gardeners are often foiled by the dense clay beneath the top layer of loose soil. Deeper down, the primary types of sedimentary rock include limestone, dolomite, shale, sandstone and siltstone. Each type of rock resists water a little differently.

Worldwide, the longest river is the Nile at 4,132 miles. In the United States, the longest river is the Missouri at 2,540 miles, followed by the Mississippi at 2,340 miles. At 182 miles, the Tippecanoe might seem like the last kid picked for dodgeball. But it has a secret weapon: biodiversity.

Why does biodiversity matter?

The Tippecanoe hosts a wide variety of fish, crustaceans and other aquatic life. It has a drainage area of about 1,900 square miles and travels through nearly 90 natural lakes. As a result, the river is home to a prolific number of species, including several endangered fish species. It also hosts nearly 50 distinct mussel species.

Stream darters are among the endangered species, including the blue-breasted, gilt, spotted and Tippecanoe darters.

Most darters are just 5-7 centimeters in length. Rainbow darters are among the most colorful of all freshwater species. They glint like jewels in the water, vivid hues of red, blue and orange. Unlike most fish, darters do not have gas bladders. Rather than control their buoyancy, darters use their tiny fins to propel themselves forward for a short distance. They sink to the bottom to rest before darting forward again.

Darters tend to live in shallow, fast-flowing sections of the Tippecanoe River. As a result, this species is especially subject to pollution. They require clean, cool water to survive. They are bioindicators: the darters’ presence is an indicator of the river’s healthiness!

Other Tippecanoe bioindicators include stonefly, mayfly and caddisfly nymphs, and freshwater mussels. In fact, the world’s largest population of clubshell mussels live in the Tippecanoe River. This and other mussel species are valuable even after death. Their empty shells can house fish eggs or insects, and eventually break down to become part of the riverbed.

Even as it occasionally changes depth and direction, narrowing in some places and widening in others, the Tippecanoe remains a valuable ecological resource in our county. You can best protect the river by learning about and enjoying it. Consider taking a canoe trip down a stretch of the river, or visit Tippecanoe River State Park!

Start your adventure

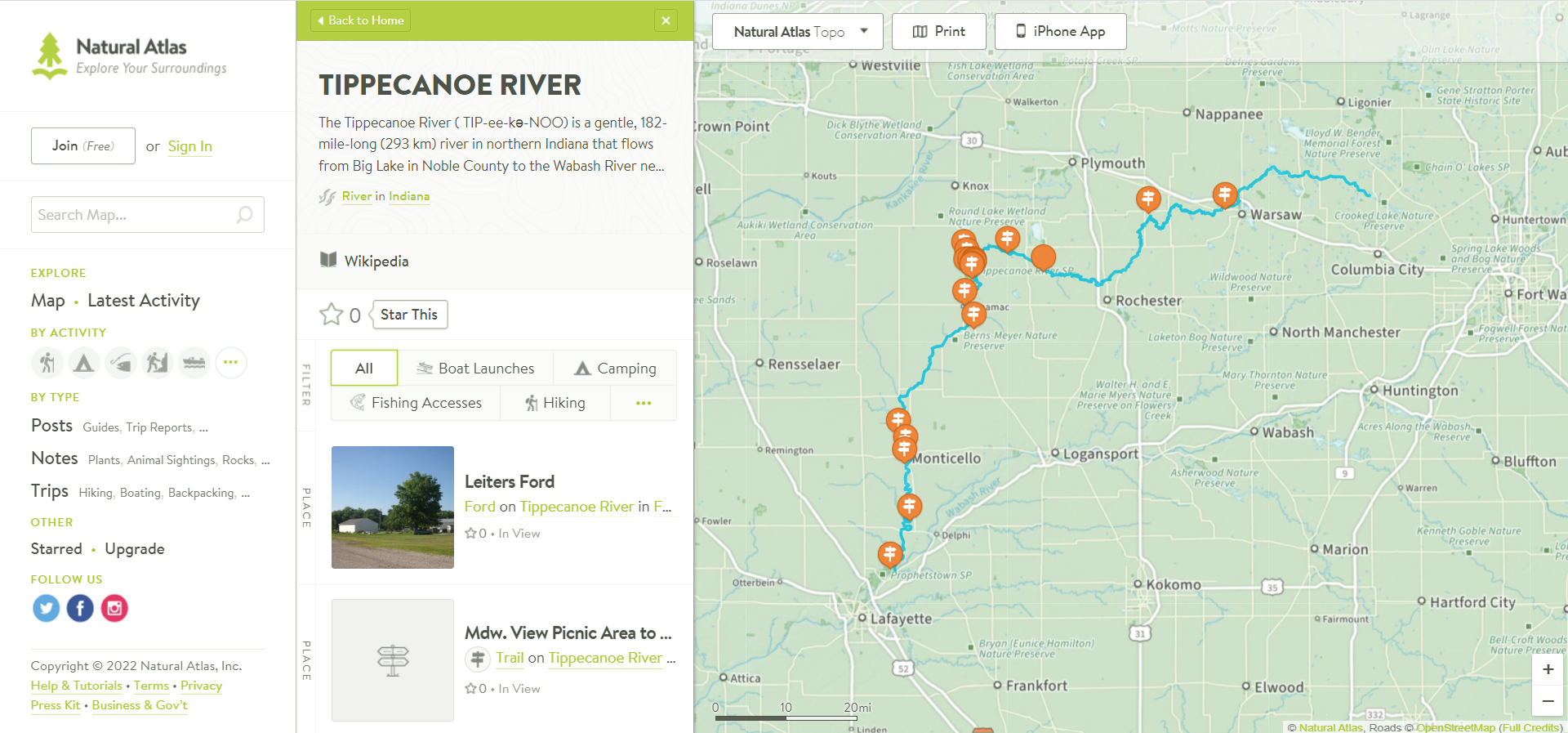

You can download and use Nature Atlas to map your own excursion! Keep track of your favorite locations and share those cool spots with other users.