Native, non-native and invasive species… what’s the difference?

You may have heard the terms native, non-native and invasive in the context of plants or animals that live in Northern Indiana. But the meaning of these words might be confusing, as well as how their differences impact the health of our natural resources.

Let’s start by defining our terms…

- Native: a species that originated and developed in its surrounding habitat and has adapted to living in that particular environment. (It can become aggressive, similar to an invasive species.)

- Invasive: a species of plant or animal that outcompetes other species, causing damage to an ecosystem.

- Non-native: a species that originated somewhere other than its current location and has been introduced to the area where it now lives (also called exotic species).

Did you know?

Although not native to our state, the peony is Indiana’s state flower. “It’s a non-native plant that has been cultivated,” said Brad Clayton from Clayton Garden Center. “It’s been here long enough and doesn’t cause economic or ecological harm.” The peony, once non-native, is now a type of naturalized plant.

“Native plants are ones that evolved and adapted to a specific area or region without human intervention,” explains Brad Clayton, expert gardener from Clayton Garden Center. In general, a native species will produce robust foliage and/or blooms once established, and quickly attract critters like butterflies and insects. They survive in both dry and rainy weather without suffering.

An invasive plant will spread and prevent other plants from growing. “They cause either economic or ecological loss,” Brad noted. “This can happen by reducing crop yields in agricultural production, or in the case of forestry production, the reduction of desirable species needed for timber.” Although beautiful in their own way, they dominate their ecosystem and don’t provide the nutrients needed by native insects and animals.

Non-native plants share qualities of both: they produce foliage or blooms and don’t take over their habitat. But they’re often not adapted to the environment, and require more care than native plants. If a non-native stays around for long enough, it’s labeled a naturalized plant. (Like the peony!)

Sometimes the differences get blurred. For example, you can have a native plant that becomes aggressive (but not invasive) as it takes over your flowerbed. In the context of a lake, blue-green algae is a native species that causes problems like an invasive would.

You can also have non-native species that stay in one spot and don’t become invasive. Most landscaping plants (especially those planted annually) fall into this category. Although not native, they also don’t disrupt their environment.

Examples of invasive species

These are common aquatic and terrestrial invasive species found in Kosciusko County.

Zebra mussels, or more specifically Dreissena polymorpha, are a species of freshwater bivalve. They are native to the Black Sea and Caspian Sea in eastern Europe, but made their way to the United States in the 1980s in the ballasts of ships. They are prolific and can quickly clop pipes and line shorelines with sharp shells.

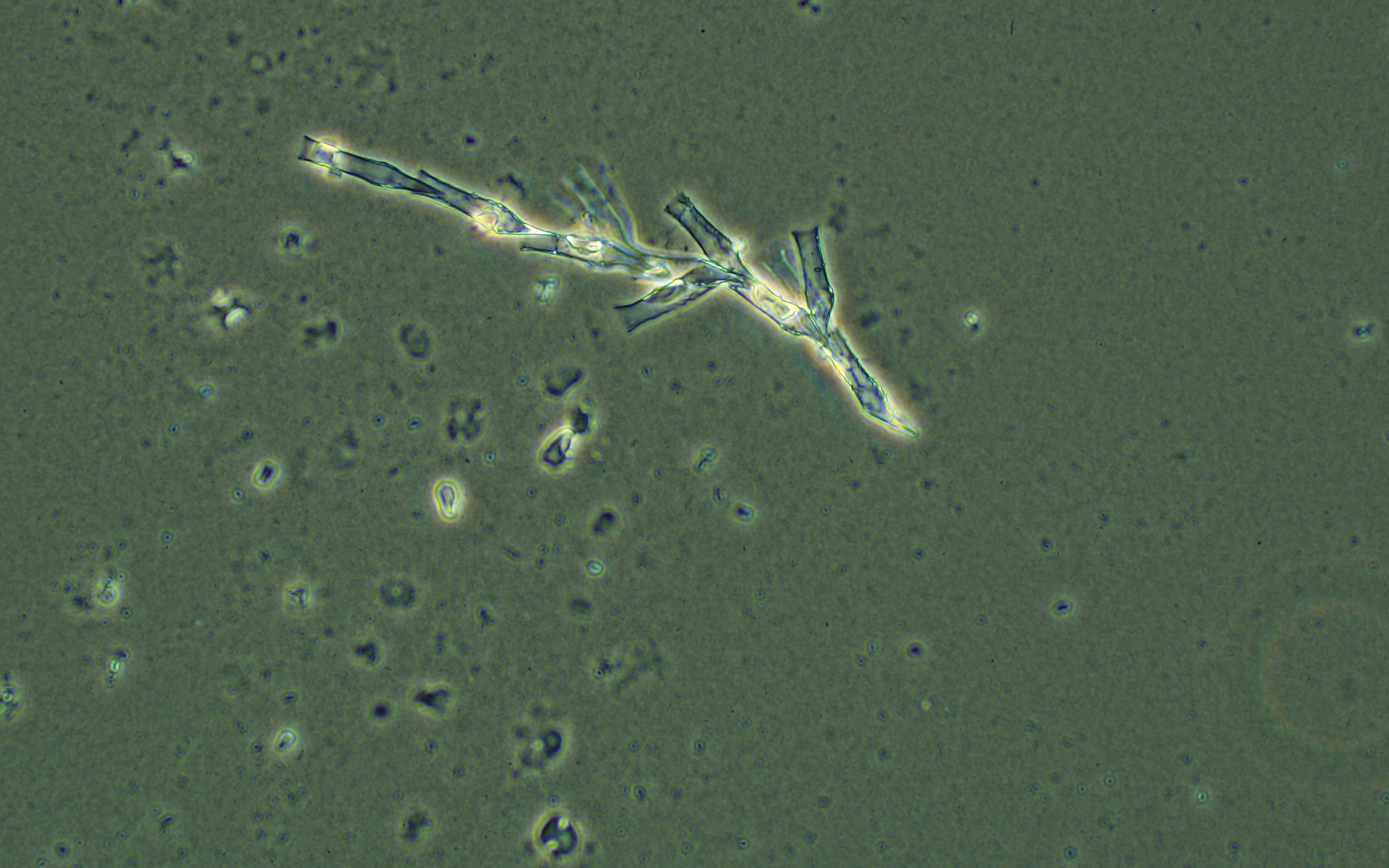

Starry stonewort is an aquatic invasive species that can grow in water anywhere from a few inches to nine meters deep. It prefers hard water and can tolerate low-light conditions. At it’s worst, the invasive can out-compete native species and create dense mats on the surface.

This invasive shrub is found in woodlands and in landscaping. If allowed to grow without pruning, they become large and dense, preventing light from reaching other plants. They grow best in “ideal” conditions: moist, well-drained soil and part-to-full sun.

Garlic mustard is a bright green, leafy plant that has small white blooms. It can quickly re-seed and spread through large swaths of woodland. It can easily crowd out native species, and it’s hard to eradicate once established.

Landscaping with native plants

The ideal native plant garden will have a balanced variety of species, much like the landscaping around the Lilly Center’s home in the Dr. Dane A. Miller Science Complex.

“The simplest way to incorporate native plants into an existing landscape is to just plant them,” Brad says. “Look for nativars, which are native plant species that have been cultivated by humans to be more desirable in landscapes.”

For example, purple dome New England aster. “Purple dome only gets 18 inches tall and 1-2 feet wide, compared to its native counterpart which is 4-6 feet tall, and 2-3 feet wide,” Brad explains. Both varieties are excellent food sources in the fall for pollinators looking to stock up before winter.

In the Lilly Center’s native gardens, you can find purple dome aster, swamp milkweed, purple coneflower, blue flag iris, wild quinine, blue-stemmed goldenrod and black-eyed susans, just to name a few! Each plant is adapted to keep the others in check and also provides habitat and food for many kinds of insects and animals.

Many local nurseries keep native plants. Reach out to them today!

Riverview Nursery

www.RiverviewNativeNursery.com

(260) 704-5092

Cardno Native Plant Nursery

(574) 586-3400

S & L Environmental

www.slenvirogroup.com

(574) 536-9879

Myers Landscaping & Nursery

www.myerslandscapenursery.com

(574) 457-5354

Heartland Restoration Services

www.earthsourceinc.net

(260) 489-8511

Clayton’s Garden Center

www.claytongardencenter.com

From land to water

How you manage your landscaping can have a big influence on the health of local waterways, including lakes, rivers and streams. Thoughtful landscaping helps prevent too many nutrients from entering the water and producing weeds and algae blooms!